Peacelines I. 1994.

“My context is unique in that I live yards from one of the most prominent structures. They impact on my life on a daily basis.”

It was a time of censorship. I was looking for a project within the wider political realm, a project that resonated with me on a personal level. Peacelines were an obvious choice. I live in an area of Belfast that is isolated, surrounded, and historically maligned. When I began photographing the peacelines, I was 28 years old and hoping for a better future. The peacelines seemed vulnerable to removal as the peace process began, this is when I started to make them history by photographing them. The series was first published in the book Interface Images by Belfast Exposed on September 31st, 1994. On this day, the first IRA ceasefire began. It was a time of optimism that lead to the Good Friday Agreement only a few years later.

Camera: Nikon F3 with various lenses.

From Peacelines to Battle-lines - Ronan Bennett

In August and September 1969, Loyalist attacks on the Nationalist areas of Belfast sparked deadly communal rioting. Fearful of fresh onslaughts Catholics formed local defence committees and hastily threw up barricades. Although primarily defensive, the barricades were an implicit challenge to the authority of the Stormont government and the Royal Ulster Constabulary. On September 9th, The Unionist Prime Minister, Major Chichester – Clarke, insisted the barricades come down, though he conspicuously failed to acknowledge the reason for their construction. When the Catholics failed to comply, their Protestant neighbours retaliated by building their own barricades. Within a few days there were more than two hundred such obstructions in the Lower Falls and Lower Shankill alone. The British Army under pressure from the Stormont Government moved to try to control the communal initiatives by erecting makeshift barriers of barbed wire and sandbags. Lieutenant – General Sir Ian Freeland, the then GOC, said, “We will not have a Berlin Wall or anything like that in this city” and at that time few thought that the army barriers would be in place for long.

But far from being “a very temporary affair” the “peacelines” have proved all too durable. They have spread from their original sites along Cupar Way and the Lower Falls, up to Springhill and New Barnsley, Lenadoon and Ladybrook; north to the New Lodge and Tiger Bay, Ardoyne and Oldpark and Cliftonville; and east to Short Strand. As events at Manor Street in 1986 showed, housing redevelopment can often be used to consolidate the peacelines. Also, certain streets that had acted as a buffer-zone for example, Bryson Street in the Short Strand, were demolished and replaced with walls during redevelopment. The “temporary” peacelines of sandbags and wire are now permanent structures of concrete steel bars and corrugated iron screens.

Belfast, of course has always experienced a high level of segregation. During the late nineteenth century, at a time of industrial growth, rural migrants who flocked to the city in search of work tended to settle in the same areas as their co-religionists. We should not overlook the extent of cross community contact in the workplace, nor the genuine efforts of trade unionists and other progressive forces to unite working-class people in the city, but the problem has always been that at times of political or economic crisis – during the riots of 1886, the upheavals following partition in 1921-22, the continuing anti-Catholic disturbance of the 1920s, the severe rioting in 1935 and so on – Belfast has tended to divide sharply along sectarian lines.

This tendency was to have devastating consequences for the people in the six counties after the establishment in February 1967 of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. NICRA’s demands were moderate; local government reform and an end to discrimination against Catholics in housing and employment. These are objectives that liberal Protestants could and should have supported. Some did – notably – but most did not, choosing instead to go along with their political leaders’ characterisation of the Civil Rights marchers as subversives and fellow travellers of the IRA. One of the great “what ifs” of modern Irish history is; what would have happened if the Civil Rights marchers’ demands had been met?

Would the Northern state have evolved into something more modern and stable, leaving behind the dark days of Stormont discrimination bigotry? Would we have seen the violence of August 1969? Would we have been spared the 3000 plus deaths that have resulted from the war which goes by the euphemism of the ‘Troubles”?.

There are those on the Nationalist side who argue that the Northern state could never have changed, that for it to do so would have been tantamount to signing its own death warrant, for the state was founded on sectarian principles and had no other rationale than to protect Protestant rule at all costs. After a quarter of a century of conflict, it is hard to take issue with this analysis, Stormont did prove incapable of reforming itself. Instead, Civil Rights marchers were beaten, attacked, intimidated and jailed. The pictures of policemen clubbing demonstrators to the ground in Derry on October 5, 1968 have become almost iconic. For most Civil Rights supporters, they crystallised a moment of stark realisation; nothing was going to change while Stormont remained.

In retrospect, the saddest feature about the period 1967-69 was the failure of the Protestant working-class to make common cause with their Catholic neighbours. As some Protestant leaders now make clear, the Protestant working-class were being taken for a ride by “the fur coat brigade”, their political leaders in Stormont, at the same time as Catholics were being subjected to discrimination and repression. The “privileges” the Protestant working class enjoyed – better access to (low paid) jobs and (low grade) housing – were bought at the expense of uncritical support for political leaders who ignored the needs of their constituents.

Though Civil Rights workers and radical students, in an effort to reach across to the Protestant working-class, stressed the non - sectarian nature of the movement for reform, the sectarian impulse, stoked up by Unionist politicians, proved too strong. Protestant crowds, supported by the sectarian B-Specials, came onto the streets of Belfast, determined to put an end to what they saw as a challenge to their position, their state, their “way of life”, their religion. The communal rioting of August and September 1969 was the worst for several decades. Eight people died; 1500 Catholic and 300 Protestant families were forced out of their homes. By February 1973, 60,000 people – ten percent of the city’s population – had moved out of their homes in what was, at the time, the biggest population displacement in Europe since World War Two.

The death and destruction was deeply shocking. Since then, of course, the situation has worsened; more than 3000 killings in the Six Counties, almost half of them in Belfast. Half of the Belfast killings (739 at the time of writing) have been classed officially as “sectarian”; of these by far the largest number of murders (549) has been perpetrated by Loyalist paramilitaries on the Nationalist community; 123 Protestants have been murdered in sectarian killings. Another 155 Catholics and 31 Protestants have been killed by the British Army and RUC.

The 1991 census shows that the trend towards residential segregation proceeds unabated. As the sectarian assassinations continue, it is clear that there is no such thing as a “safe” area in the city, but it is grimly ironic that among the most dangerous places in Belfast are the areas around the so-called peacelines, as the shooting at Springfield Park/Springmartin earlier this year of Paul Thompson indicates. Here people live in a constant state of anxiety; sectarian tension never goes away. One generation has come to maturity since peacelines first gave physical expression to already existing psychological and instinctive boundaries. A second generation is growing up in conditions even more polarised and divided than those experienced by their parents during their youth. What lies in store for the third generation?

I look at Frankie Quinn’s photographs and am appalled at the images of urban desolation around the peacelines; and I am appalled at the images of a landscape that reeks of fear and tension and blighted life. But these pictures also provoke anger – anger because these peacelines, which are in reality Battlelines, are an enduring symbol of massive failure. The failure is not of the Nationalist community on whom the “Troubles” are so often blamed, but the British government. The peacelines that British soldiers built and continue to build are the sorry and inevitable outgrowth of a policy, successive British governments pursued since partition; they acquiesced in the creation of the sectarian state; they supported it as long as they could; they continue to underwrite the Unionist veto on the constitutional changes without which sectarianism and segregation will continue to prosper. The peacelines are, in every sense, a British creation. The presence of one is inextricably linked to the presence of the other.

Ronan Bennett

August 1994

Review of Interface Images by Máirtín Crawford

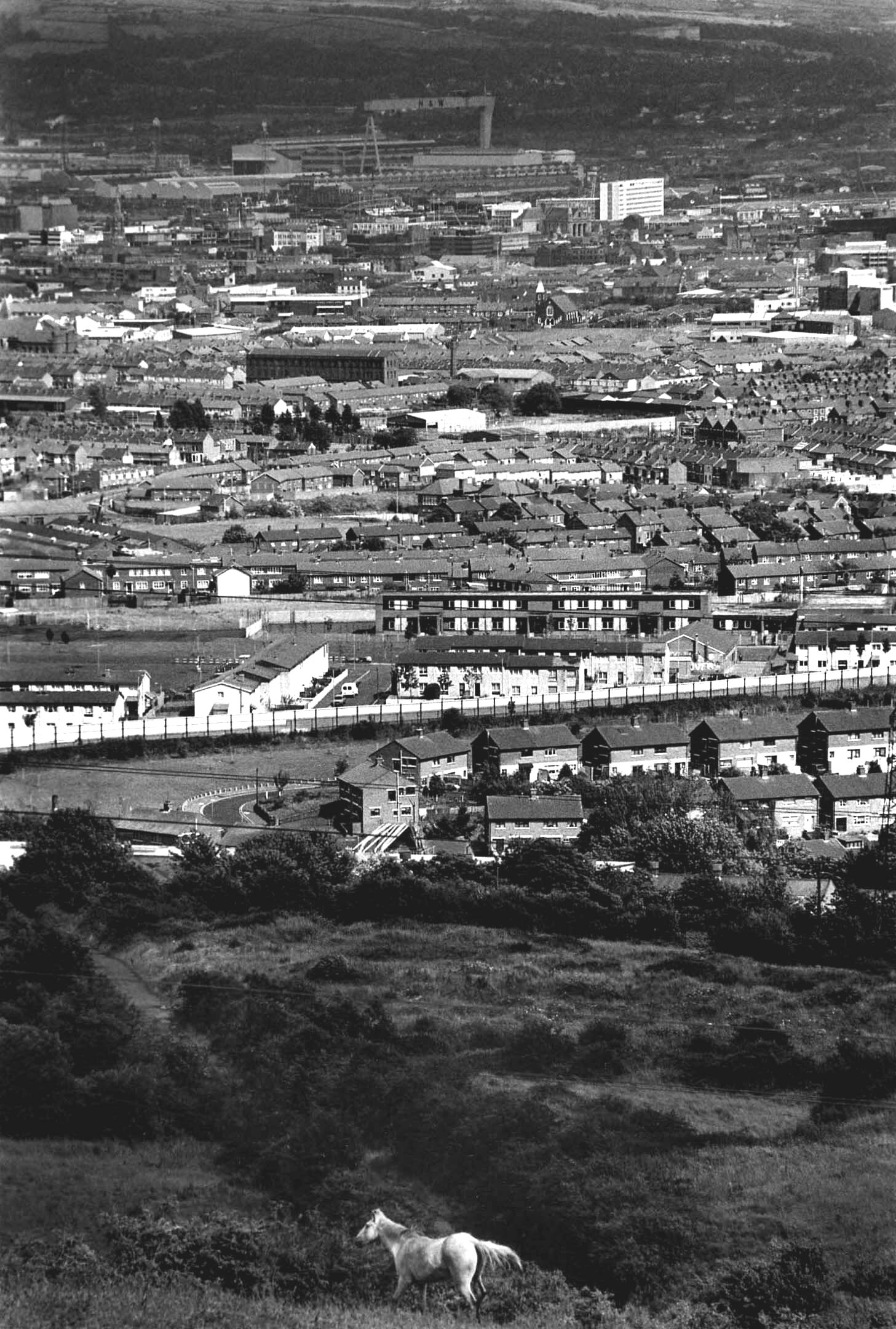

Frankie Quinn’s stark photographs of Belfast’s communal dividing lines paint a dark and pessimistic portrait of a divided city.

The ‘Peacelines’, first erected as a temporary measure in 1969, have become a familiar part of Belfast’s urban geography and they act here as the physical reminders of how difficult any act of reconciliation between the two communities they divide will be.

Quinn’s photographs tell a story of division and the more than temporary nature of the interfaces – neatly illustrated by the third photograph in the book showing the line dividing the Falls from the Shankill – ivy has colonised most of the walls and stretches up along the corrugated iron of the top of the fence, a twice - ironic juxtaposition of nature against construction.

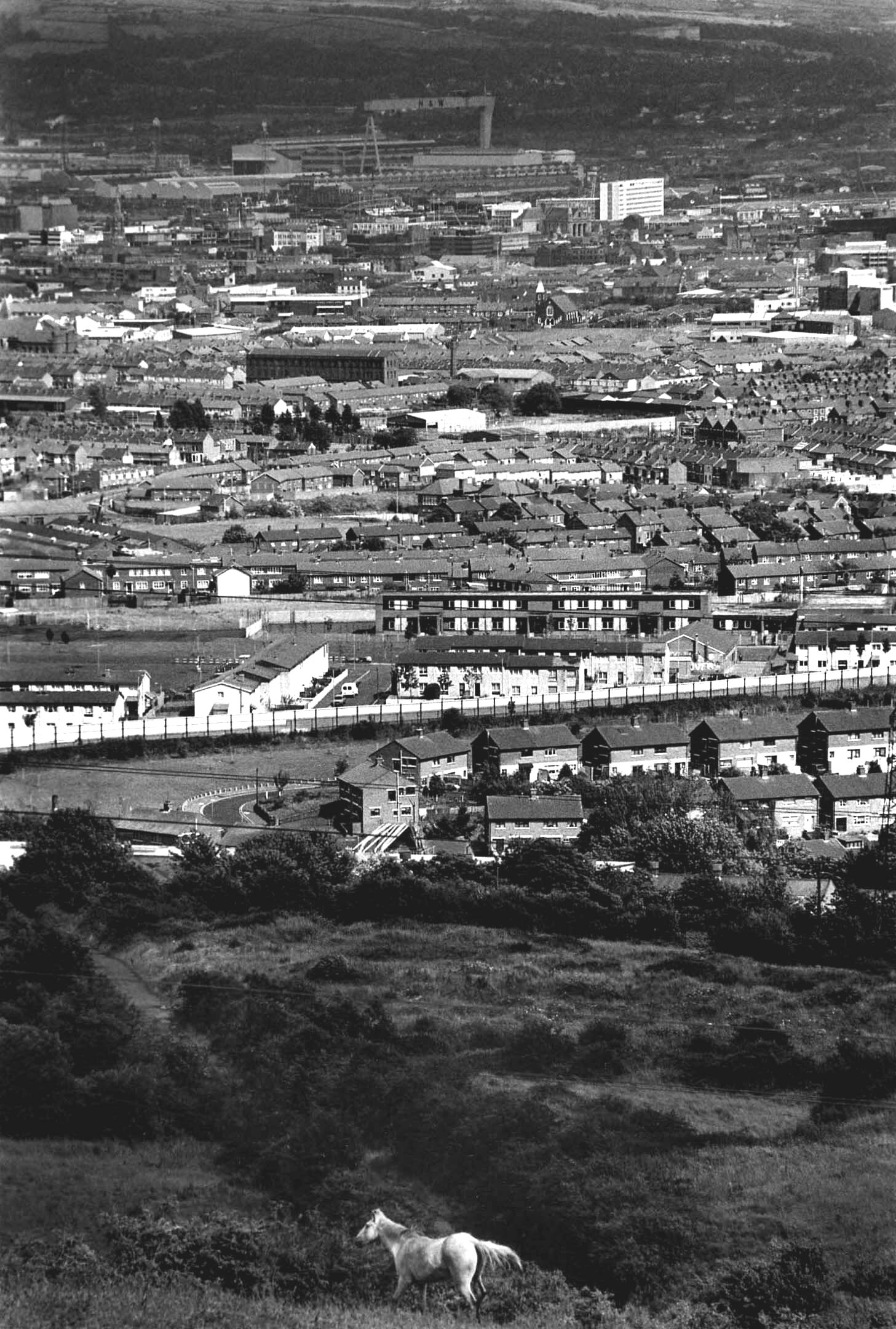

The next photograph in the collection, taken from high above looking down, showing a part of the Short Strand part of Belfast, is almost surreal in its depiction of the back to back yards of terraced houses, neighbours shut off from each other by the presence of the Peaceline that rises ominously above and between the houses.

In other photographs the walls act as a backdrop to the daily lives of the citizens of Belfast. Women shop with their children along divided streets, kids play at being soldiers/IRA/UVF/whatever, teenagers lounge on the sofas collected for annual bonfires, surrounded by wood, hemmed in by the peacelines, designed to keep them in, others out, all away from each other.

What is also apparent from even a cursory glance is the absolute dereliction and desolation of the urban landscapes portrayed – tiny bricked up terraced houses, areas redolent with poverty peopled by those whose faces speak grimly of life after twenty five years of ‘temporary measures’ and failed political initiatives. There will be no grand Berlin – wall – like deconstruction of these dividing lines, rather a slow and tortuous road towards understanding and reconciliation. Frankie Quinn’s powerful and haunting photographs remind us of how long that road could be.

Máirtín Crawford

The Big Spoon

Winter 1995.

Review of Interface Images by Ian Hill

Belfast Exposed is a community resource photographic centre recording its own visual responses to the city’s plight and Frankie Quinn, a founder member, is one of its stars.

His current exhibition, Peaceline – 25 years of division, seen briefly before and not too well displayed at the group’s own place, is now elegantly and chillingly presented in the Old Museum. The sixteen, bigger than A4, crisp, black-and-white prints are wry, poignant, evocative and angry in turn, visual observations on the city’s peacelines, from Ballymurphy in the west to the Short Strand in the east, from the absurdly inappropriately named Alliance Avenue in the north to Roden Street in the south.

Begun in despair in 1969 by a British Army unable to contain violence emanating from both communities, their erection was accompanied by a promise of their impermanence. They are, of course, still with us, clematis-clad as the photographer shows, for instance, on Cupar Way in the Shankill, and indeed at a fringe meeting at the recent Economy of the Arts Conference in Dublin the imaginative and provocative suggestion was made that these Berlin Walls should not be demolished; rather, with EC arts millions, they should be preserved as a focal icon.

Be that as it might be, Quinn’s often stunning images, deserve study. Inevitably children (as in the recent media front page responses to the ceasefire) feature strongly, playing with replica guns, playing over army vehicles, standing grubbily, dark angels, defiant or running about their business as Belfast burns behind them. Alternatively old ladies peer suspiciously from the doorways of mean, red-brick terraces, or thick-stockined and head-scarved, look back as JCB’s demolish. Hard men lounge on 11th Night bonfire detritus; behind them, runs the device One Queen One Crown No Pope in Our Town. Houses stand in isolation in a grey mist.

In a particularly surreal vision, worthy of Dario Fo or Duchamp, a clean, architectural designer-feature separates adjoining, neat, cherry-treed gardens off the Albertbridge Road. In another, a man steps through a door in a vast, dark, oppressive wall, entering perhaps, another land. An accompanying book Interface Images can not quite do justice to Quinn’s skill as a printer and Ronan Bennett’s contentious introduction - in which not one iota of responsibility for the city’s woes can be laid at the door of the Nationalist community – also does not appear to do full justice to the breadth of Quinn’s perceived perceptions.

Ian Hill

The Irish Times

January 1995

Review of Interface Images by Brendan Murphy

Is it Bridget and Sammy or Seamus and Iris?

It is impossible to tell which is the Catholic is and which is the Protestant. These east Belfast neighbours, a man and a woman who have probably never met, stand metres apart in their small gardens which run back to back. They can’t see one another because a wall separates them, but they are brought together by Frankie Quinn’s camera lens.

Frankie got a bird’s eye view to take what, for me, is the definitive picture of the peacelines that divide Catholics and Protestants in Nationalist and Loyalist areas. The picture is one of fifty-five black and white prints about the Belfast peacelines.

It was a difficult assignment because the peacelines have a oneness or sameness about them, but Frankie has captured life behind both sides of the wall. In the images there is fear, despair, humour, tribalism and everyday life.

There is the woman who cleans her windows inside a mesh cage which protects her from petrol bombs and bricks. There is the wee man going past a burning bus carrying his messages – with an expression saying, “Never mind the riots, I’ve got to get the dinner home”. There is the apprehensive young boy peering from behind the frosted window of a front door shattered by a brick or a stone. At Alliance Avenue, Frankie photographed kids looking through the slits in the Peaceline fence with the humorous caption, “Mister, can we have our ball back”.

These images, beautifully printed, stand on their own and are important because, if the peace process is successful, these walls may disappear. The book will be a grim reminder of the past twenty-five years.

Had it included captions or an anecdote with each picture, it would have been a more important social comment. We are not told when the first Peaceline was erected, how high the walls are, or how many of them exist.

Having covered most of the peacelines as a press photographer, I know most have a story to tell. For example, Frankie has taken an excellent picture of the last house in a street beside the Manor street Peaceline. But there is no caption to tell us how the occupants refused to move after years of bombs, bullets and bricks which drove their neighbours from their homes. The houses were then demolished.

Perhaps if the walls do come tumbling down, Bridget and Sammy or Seamus and Iris will get a chance to see and meet one another over their garden fence and become true neighbours. But that is a picture for another day.

Brendan Murphy

Causeway magazine

Winter 1994.

Review of Interface Images by Bill Kirk

Interface Images published by Belfast Exposed Community Photography Group faces squarely, yet often with ironic humour, the harrowing sectarian problems at the heart of Belfast City.

Of the three volumes, the other two volumes are ‘Belfast’ by Christopher Hill and Jill Jennings and ‘Parallel Realities of Northern Ireland’, it alone stands free of pretension and elitism and reveals the coming to visual maturity of a fine young photographer in Frankie Quinn.

It is admirable in that it is truly home grown, for Quinn lives there and therefore cannot be accused of exploitation.

His easy use of the wide angle is at once startling and surreal and evokes William Klein at times and at others Robert Frank, and maybe a little dash of Brandt!

But somehow when looking at these photos I become convinced of the veracity of the work and of the unlikeliness that Frankie was thinking of any other photographer at the time.

My favourite is about two thirds of the way through and shows a boy standing centre frame at nightfall at the peaceline, over which blazes (probably) a Loyalist bonfire. On a gable is the Biblical quotation from the Sermon on the Mount; ‘blessed are those who hunger for justice’. Three images back is an amazing photograph of the canvas screen used during marches to prevent the other side from taking offence.

Surprisingly for such a fresh work, history has already overtaken it in some ways. In Ronan Bennett’s introduction he states that the sectarian killings continue unabated.

Bill Kirk

LinenHall Review

Winter 1994

Peacelines I. 1994.